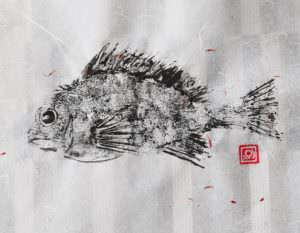

gyo “fish” + taku “rubbing”

Gyotaku 魚拓 dates back to the mid-1800s, the method of documenting fish caught, proving claims of size and appearance by Japanese anglers. The oldest known prints were commissioned in 1862. Over time, fish printing evolved into an art form, still practiced today. A skilled gyotaku artist can create beautiful images that catch subtle details and textures. A print, well-executed, yields accurate imagery and details that become useful for scientific study as well taxidermy – a place where art and science merge.

In the earliest prints, inks or pigments were applied directly to one side of the fish capturing size, shape, surface texture, and delicate vein or scale pattern. As the art evolved, embellishments with ink and paint were added to emphasize these natural prints.

Tools Your Muse Rubber fish, found on the web, were detailed sufficiently for this practice run. Look for pliable fish with scale and fin details. If choosing edible fish, consider using food-grade squid ink or other pigments, then print your fish and eat it too.

Your Muse Rubber fish, found on the web, were detailed sufficiently for this practice run. Look for pliable fish with scale and fin details. If choosing edible fish, consider using food-grade squid ink or other pigments, then print your fish and eat it too.

Paper Authentic gyotaku uses washi (Japanese papers) made from natural substances like “kozo” or paper mulberry bark fiber. But traditional Chinese papers called “xuan” papers, work too. Any thin, flexible Eastern paper or similar that somewhat wrap around one side of your fish are needed. Most examples in this article are from Paper Connection’s Meteor Series, but there are many more options.

Ink or paint? Traditionally ink is sumi, a water-based ink made from carbon (burned substances like plant materials). You could try block print, acrylic, or oil paint. In our examples, food-grade Squid Ink was our choice. You can use a tampo or dauber, a piece of foam with a handle, or even a cosmetic sponge, to apply the ink. We used a brayer on a glass sheet for ink application. One could use another flat surface or employ a paintbrush to cover your fish. Have several pieces of scrap paper for your trials before utilizing your quality papers.

Traditional and Hybrid Methodologies

Two traditional methods used are kansetsu-hō and chokusetsu-hō. With kansetsu-hō, you take your fish and press wet paper around the up-turned side. You carefully ink your paper to pick up the details of the fish below. Allow the paper to dry, then carefully peel it away from your fish. This method produces a single print from a single fish. With chokusetsu-hō you ink the body of the fish. A piece of paper is placed over the fish and carefully pressed against it, which picks up the details and shape of the fish’s body, and then the paper is removed. The advantage of this method is that one inking can provide more than one print.

The video deviates only slightly from chokusetsu-hō. The fish was rolled with squid ink using a brayer and then covered with paper, using slight pressure and a bit of gentle feathering in areas you might want to emphasize. The paper was ‘peeled’ away from the fish.

We used block print and squid ink. The block print ink was a bit tacky and kept the paper in place. Gentle peeling was needed, but the results were just great. With the squid ink, there was less tackiness with favorable results.

For a first-time try, the process was straightforward and forgiving, and in some cases, additional embellishments were added. The paper used changed the feel. It’s rather exciting to see how the ink and paper respond to your image. Carving the insignia went quickly as well.

Now it’s your turn to experiment and get back to us. We look forward to hearing about your results.

Check out our Monthly Subscription Service and Shop Paper Pastiche!

2 comments

Rona Conti

Your explanations are excellent with all details covered. I would love to take a workshop to learn this process as this is y best way of learning. Please consider giving a workshop.. Best, Rona

Paper Woman

Your feedback means a great deal. Thanks Rona.

If you find yourself in Kansas City I’d be thrilled to put together a Gyotaku printing workshop.

Loved checking out your work as well : )

Best,

Fricka (author/artist)