Maybe you have dabbled in alternative printing for photography, maybe you miss the good ole’ days of film and a 35mm, or maybe you look back at historical photographs over a century ago, and wonder, ‘how did they do it?’

Regardless of which of the above categories you may fall into, you will be inspired and accurately informed by Lindsey Beal, a Rhode Island-based master of many arts. Historic photographic processing is an amazing return to when photographs were produced before the advent of film. Lindsey is a pioneer in this field.

The Newport Art Museum, here in RI, will be showing her works, along with Ron Cowie. The exhibit is called New Light Through Old Windows and it opens this Saturday, January 21st until April 16th, 2017. There will be an artist talk at the museum February 9th @6pm.

We were thrilled that Lindsey took the time to answer our questions and explain her art, which crosses over into many worlds, and times.

If you are a photography aficionado, paperphile, or an educator, please grab a cup of tea, sit back and enjoy our conversation with Lindsey Beal.

Getting to Know Lindsey Beal:

PCI: Please tell us a little bit about your work and background: what do you do, where, and what inspired you to pursue photography. What inspires you to champion early photo processing? Do you combine any modern technology in your methods; how so?

LB: I am a photo-based artist who lives in Providence. I work in a studio in Pawtucket in one of the mill buildings where I make books and print photos. I teach a course on photography books at RISD, a handmade photography on fabric & paper course at MassArt, and am an adviser and core faculty in NHIA’s MFA program. I graduated with my MFA in photography from the University of Iowa and a graduate certificate in Book Arts from the University of Iowa Center for the Book. I picked up photography as a freshman at St. Olaf College, a liberal arts college in Minnesota.

LB (cont’d): Although I worked in all mediums, photography is what stuck and what I am most passionate about. However, I do not generally call myself a photographer but a photo-based artist—someone who uses photography in her work, just as I do printmaking, sculpture, books or papermaking. However, photography is the constant in all my work. I mainly work in historical photographic processes—photographic methods that existed before the advent of film. It can become very painterly and overlaps with printmaking. I like bringing in digital images, inkjet printers or photo editing software to help me create negatives from which to print.

PCI: For those who may be new to the idea of returning to the early methods of photograph processing, what does it mean to be a historic processes photographer?

LB: There are variety of different viewpoints and approaches for those who use historic photographic processes. Maybe they are passionate about history, maybe they want to be in control of all the aspects of photomaking, maybe they want to incorporate a more hands-on way of working, or maybe it fits their content better than analogue or digital photography. The reasons are very diverse, just as it is to use one process over another. For some, if you know one process, you at least learn others, even if you do not work in them. At its most basic level, these processes use chemistry that coats a surface like metal, glass plates or paper, exposed to light and then processed through various chemicals to develop or fix the image—just like darkroom photography since this is how photography began. Sometimes you end up with a unique image (positive), and sometimes you use a negative to make the plates or prints. With something like photogravure, you ink up a photographic plate and run it through a printing press to make multiples.

PCI: Do you feel that this field of photography is making a comeback, or becoming popular with colleagues, peers, or the next generation of photographers and/or printmakers? Why is this so important in such a digital age?

LB: Yes, since the advent of digital photography, the desire to return to photography’s roots and work more hands-on has grown. There are generations before me who led the way in this, and generations younger than me that are enthusiastic about it too. The benefit is now we can use digital images and go back into the darkroom by making our own negatives on printable material that resembles overhead transparencies. Darkroom materials like film and paper are becoming harder and harder to find, but you can go back to processes that existed pre-film in order to work in the darkroom with these turn of the twentieth century processes. You are in complete control since the chemistry is made from scratch and you choose what kind of paper, glass or metal to print onto. The processes are slow but I think that is valuable in today’s world. Sometimes it takes longer to produce bodies of work but for me it is important to have my hand in some part of the process.

Relationship with handmade paper:

PCI: How does handmade paper, or Japanese handmade paper, (washi), configure with your work?

LB: Handmade paper doesn’t always factor into my work, but my knowledge of paper, and its unique qualities always influences what type of paper I print onto. I am a paper nerd and must go see the paper in person so I can feel it before buying, whether for handmade books or as printing surfaces. I always encourage my students to go in person to pick out paper—it’s important to have local stores like PCI that you can visit to do just that.

PCI: What qualities of washi do you look for in choosing which paper is right for the printing/photo processing effect that you desire? How do these qualities affect your work technically and aesthetically?

LB: I look for something that has a good wet strength since my processes require coating the washi with chemistry, allowing it to air dry, exposing it to UV light and then developing it in multiple trays of chemicals or wash out baths. I also look for ones that dry flat—I need a good seal between a negative and the coated paper because if the paper dries wrinkly, my photos will be out of focus. While I can use supports to gently bring the paper out of the chemistry or handle them carefully in the water baths, I prefer to do more testing to find a paper or fiber I do not have to so carefully monitor. After that, if I know that the paper reacts well, the look and feel of the paper needs to fit my content and aesthetics.

PCI: As a papermaker, what do you appreciate about traditional Japanese papermaking and using washi?

LB: I love how in Japanese paper making, you can do it all yourself without a lot of expensive equipment. You can cook, and pound the raw fibers—you do not need a mechanical beater to do so. Similarly, with the vat and drying system. The most expensive materials would be the molds. For me, although I primarily make Western paper, Asian papermaking techniques seem more accessible without a lot of equipment. That being said, I really struggled with traditional Japanese papermaking at the University of Iowa! Now that I often purchase kozo paper I print on, I appreciate it more because I know what went into making it.

PCI: How did you come to know about Paper Connection? How did PCI help navigate you through the world of washi?

LB: I moved to Providence immediately after graduating from the University of Iowa Center for the Book Certificate program where I mainly focused on papermaking. The greater papermaking community is a small but supportive one, so Paper Connection was suggested as a good resource to buy paper as well as meet other paper nerds like myself. Lauren was also helpful when I needed washi for a specific project and picked out a variety of papers for me to test. She was also a huge support for papermaking workshops at AS220 for which I assisted the instructor May Babcock.

PCI: The arts community in RI truly echos-not 6, but 1 degree of separation!

The Venus Series:

PCI: What inspired The Venus Series? What kind of photo application is used?

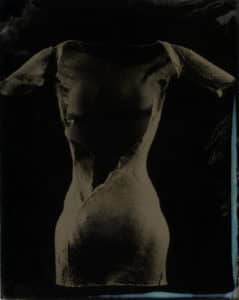

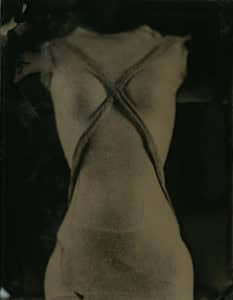

LB: I was curious about the history of the Venus figurines from around the world. They are a diverse group of pre-historic figurines whose meanings have eluded archaeologists for centuries. Each generation finds new meanings in them, as do new generations of artists. I was always drawn to their mystery and the wet plate process further emphasized this. They began to be discovered at the height of wet plate collodion’s popularity so both historically and aesthetically I tied the two processes together.

PCI: Were any sheets of washi used for this series of images?

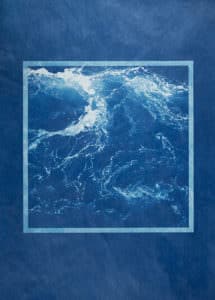

LB: I did not use washi in this project, but did use it for another series “Commonplace” where I printed social media images in cyanotype (like architectural blue prints) onto kozo paper that I later waxed, and handbound into a book using a Japanese stab binding technique. For “The Venus Series” I overbeat raw flax in a mechanical beater. I pulled the sheets and allowed them to air dry around forms. This paper created the figures for which “The Venus Series” is based in. The photographs were taken with the wet plate collodion process (many know it as the tin type process), that was popular during the Civil War.

PCI: Wow. What does it mean for you personally that Newport Art Museum is showing your work, as a RI resident?

LB: I have lived in RI for five years now. Originally from Maine and Minnesota, I also lived in Portland, Oregon and went to graduate school in Iowa. My husband and I moved to Providence for his training at Brown’s Family Medicine residency at Memorial Hospital in Pawtucket. After he finished his training we moved to Wickford for two years and are now permanently back in Providence. For me, showing in Newport is a great honor—I find the history of the area fascinating and attend the Newport Folk Fest every summer. I was thrilled when Francine Weiss, the new curator at NAM, wanted to show my work with Ron Cowie, a friend and colleague of mine. I have a few upcoming shows in RI this year so am happy to be showing in my state!

As an educator:

PCI: What do you try to instill in your students as far as carrying on the tradition of this type of photography? Or photography in general?

LB: I try to instill in my students a knowledge of photographic history since they should have a grounding in it if they are working in the historical processes. However, I am not a purist and want to take these historical processes (or alternative photographic processes or handmade photographic processes, depending on what you prefer to call them) into the 21st century. I create digital negatives to print from and find it is a great way to get students back into the darkroom—you have more flexibility. I also want them to experiment with image making and surfaces types. What is the most important to me though is that the process is tied to the imagery somehow—if you are working in these processes you often must justify your use of them, but I think for good reason—why are going to these lengths to print in these methods in today’s world? Tie their background—why were they used, what kind of imagery, who used them, etc.—into the work.

PCI: For those interested in learning about historical processes photography, what advice would you give? What papers work?

LB: The papers vary from process to process. In general, something that is pH neutral, has a good wet strength (can hold up in multiple water baths and coating with chemistry). A good place to start is a good cotton watercolor paper (hot press if you want to see the image well but cold press can change the images’ message). Asian style paper like kozo or mitsumata are perfect since they have a great wet strength and take wet chemistry well. Sometimes they need more support in their handling but are beautiful papers. Once they learn various processes and feel comfortable with it, I try to get my students to think about the work’s content and how the surface reinforces or matches the concept. I try to instill in my students a sense of experimentation and play or risk taking. Some of my students have printed on phone books, newsprint, paper towels—whatever they wanted to try out. Obviously that work is not archival but I appreciate the surface experimentation!

PCI: Lindsey, we thank you so much for talking with us during this very busy week of yours. We also thank you for your support of handmade paper, this amazing method of photography, and for sharing your knowledge through teaching. Congrats on the show!

For more information on Lindsey Beal, please visit her website: lindseybeal.com

For those in the southern New England area, an upcoming show will be held at UMass Dartmouth Gallery: Singular Repetitions, a 5 person monoprint show. Visit Lindsey’s website and social media to find out more.