Recently we corresponded with New York-based collage artist Deborah Hillman, who has been using our lokta papers in her lively, abstract compositions. She shared with us how she explores language, synesthesia, art history and anthropology, and encapsulates these ideas into stunning works of art.

Here is our conversation with Deborah:

PC: How would you define your artwork, technique, and paper application?

DH: I often refer to my artwork, in general, as “art of the inner world.” My images come from dreams, imagination, and looking inward—yet they’re inspired by shapes, colors, and textures found in nature. I frequently gather leaves, stones, branches, seed pods, etc., and bring them home to study their delicate lines and subtle shadings. Although I’ve painted on canvas and paper, I love collage and mixed media, and that has been my focus for nearly a decade.

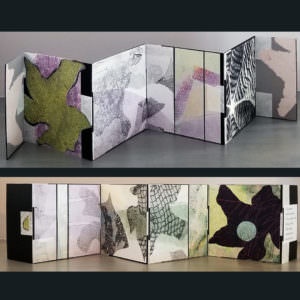

The ground that I use most often is cold- or hot-pressed watercolor paper (although, for small cards and envelope seals, I work directly on lokta). For works of all sizes, I scissor-cut shapes from sheets of lokta paper, attaching them to the ground with acid-free glue (primarily glue sticks). Most of the time, if acrylic is part of a piece, I add it later, though sometimes I paint on a shape before it’s attached. My largest lokta paper collage is 22×30 inches. The smallest are less than three inches square and used as envelope seals. Along with titled works of various sizes in between, I’ve kept up a series of untitled greeting cards. They, and their matching envelope seals, are one of my greatest pleasures and often set the stage for larger pieces.

PC: Any insights into your process and current projects you would like to share?

DH: I recently developed a fascination with asemic writing, and that’s what I’m now exploring in my art. Asemic writing “looks like” writing but lacks semantic meaning. It has no communal alphabet or shared pictographic symbols. Using a pen or brush to create spontaneous asemic writing encourages awareness of movement and feeling, aesthetic and emotional responses. It offers a window not only into the physical act of writing, but also into the way that writing expresses subjectivity. So far, I’ve used asemic writing not as a sole feature, but rather as an element of collage—a visual poem. My art-making process tends to combine, in roughly equal measure, spontaneous, intuitive ways of working and much more deliberate approaches. Artworks that “fail” can often be turned into bookmarks, cards, or seals, and always they offer a new idea or lesson.

PC: Why do you create?

DH: Being creative brings me joy. It calms and uplifts my spirit. It’s meditative and playful all at once. Creating, to me, is a vital part of what it means to be human, and art is a way to find and communicate meaning. There’s also an inbuilt imperative I feel to make things with hand and heart, whether a mobile, painting, collage, or tiny envelope seal.

PC: When did you begin to work with non-Western style papers in your artwork?

DH: It started during my time in Vermont. I’d moved there from New York City, an anthropologist keen to explore a life more focused on art. I first discovered lokta paper in one of the local shops, and after I tried it, it quickly became “my” medium. That was roughly 2010, and now I’m back in New York, still exploring my love of handmade lokta (paper).

PC: What sources of influence do you draw from your background in art history and anthropology?

DH: I majored in art history in college and also studied sculpture. Much of my work as a doctoral student related to dreams and culture. Decades later, the anthropology of consciousness still absorbs me, and I’ve continued recording and working with dreams. I see that art history and anthropology quietly enter my art, as both are rich with imagery that inspires a sense of wonder. Still, I don’t actively draw on those streams so much as allow them to surface. They’re part of the iconography I carry. Matisse, Klee, Miró, and Calder are some of the artists I love. People have noted their influence in my work. My images also allude, from time to time, to material culture, as seen in the series called Beaded Rattles, Spiritbowls, and Talismans. I find in my work an abundance of geometric figures, as well—the “form-constants” first identified by psychologist Heinrich Klüver. They consist of shapes such as lattices, vessels, cobwebs, and spirals, which often show up in altered states, transcending both time and culture. They’re readily seen in Paleolithic rock art.

PC: Can you describe the importance of paper (or other mediums) in your work, what type of

paper (medium) you use most? What resonates with you about that medium?

DH: The thing I like most about handmade paper is its sensory qualities—its many and varied textures, colors, thicknesses, personalities (from rough to smooth, and from strong to almost ethereal). Lokta paper, in particular, resonates with my spirit. It is its own form of art, representing both skill and cultural tradition. I’m attracted to it for its beauty and tactile feel, as well as the many possibilities it holds. Also, the fact that it’s acid-free and environmentally friendly fulfills criteria I look for in art materials.

PC: How have you found working with paper from Paper Connection? The work you have shared with us uses lokta, could you provide any insights, elaborations, or details in the process of working with this kind of paper?

DH: Over the years, I’ve come to know the versatility of lokta (paper), as well as some of its trickier characteristics. Because its surface texture and thickness can vary from batch to batch, some of the sheets are denser and smoother (less fuzzy, that is) than others. Those are the ones that do much better accepting acrylic paint, especially the dot technique I frequently use. Sometimes, when I’ve completed a piece, I see, in the photograph, that tiny loose fibers of lokta still cling to the surface. I gently remove them with a sweep or two of a soft hake brush (and try to remember to do that right away when a piece is finished). I’ve found that some of the colors bleed when moistened with an adhesive, and those require extra care to prevent unwanted stains. (It happens especially with saturated blues.) Although I use scissors most of the time, lokta can also be torn, and that produces a pleasantly ragged edge. I like not only the process of working with lokta paper itself, but also learning its history and how it’s made.

PC: Are there questions no one has asked concerning your creative process, philosophy, or

recent experience you’d like to share?

DH: I think it’s important to say a few words about my synesthesia, a trait that enlivens my day-to-day sensory world. I see, for example, letters, numbers, words, and names in color, and sounds have color, texture, shape, and movement. It is an integral part of the way I perceive the world around me, appearing in dreams as well as in waking life. It wouldn’t make sense to separate that experience from my art because it’s fundamental to how I’m “wired.” I’ll add, as well, that I currently belong to the Riverdale Art Association and show my work primarily in neighborhood venues in the Bronx. My handmade cards are for personal use as gifts to family and friends. They are a special joy to make and send. I’ve chosen a fairly simplified life, without a car or smartphone, and treasure lengthy stretches of solitude. And now that I’ve reached my elderhood in a deeply troubled world, it’s clear how much we humans need the healing power of art, a source of hope in every corner of our fragile planet.

PC: If you could converse with any artist present/past, who would it be and what would you

ask?

DH: That’s a question that lures my mind through time and in many directions; still, I’ll say my friend and painting mentor, Bonnie Whittingham. Bonnie—known for Provincetown harbor scenes and moody harlequins—was filled with creative intensity. She died, at the age of 76, in 1997. “I let the canvas show me who I am,” she once declared—an observation that left a lasting impression. Perhaps I would ask her to comment on the work that I’ve been doing, so different from hers, yet influenced by her deep artistic passion. I would want to make us tea and reminisce for a while. Out of that would come a lot more questions!

PC: Thank you Deborah for sitting down with us, for sharing your insight and creative process, and for reaching out with images of your lovely work!

We always love to see our customer’s work, so if you’d like to share images and possibly be featured on our site, reach out to contactus@paperconnection.com.

Images courtesy of the artist.

1 comment

catherine curtis

Thank you for this informative piece and thank you to the artist for bringing this wonderful work into the world.