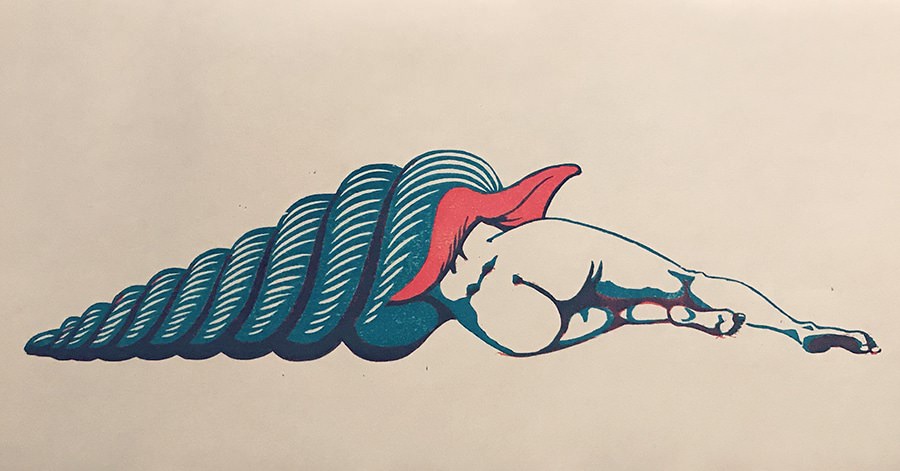

With expressive and thoughtful line, Nichol Markowitz‘s work engages the fragility of memories and our conceptions of the self.

With expressive and thoughtful line, Nichol Markowitz‘s work engages the fragility of memories and our conceptions of the self.  In her words: “As a species our history is preserved through the collective human consciousness; our bodies vessels for the past and the present, knowledge, memory, legends and thought.” The imagery is evocative and driven by her desire to “to transform these fleeting moments into monuments to the manipulated, revered, invented, and ingrained histories that define us as a

In her words: “As a species our history is preserved through the collective human consciousness; our bodies vessels for the past and the present, knowledge, memory, legends and thought.” The imagery is evocative and driven by her desire to “to transform these fleeting moments into monuments to the manipulated, revered, invented, and ingrained histories that define us as a

species, a culture, and as individuals.”

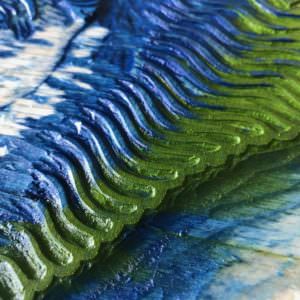

She utilizes a multiplicity of techniques including mokuhanga, copper-plate etching, and Japanese scroll mounting. In her artist statement, Nichol emphasizes “Process is an essential component in the creation of my work,” concluding that it “is not merely a means to an end but a meditative experience during which the physicality of carving a woodblock or etching a plate determines the way the image is brought into being.

Q: Where do you source your imagery?

My source material consists primarily of photographs and is almost completely derived from my ongoing collection of found and personal photographs. The personal photographs include both family photographs going back to my great grandparents as well as a large catalogue of nature and plant photographs that I have taken myself which I use as both both references for new images and for photo-transfer elements in my works. I am also incredibly inspired by natural forms and frequently reference books with photographs or scientific illustrations of plants, flowers, shells, human anatomy and other natural forms.

Q: Who or what do you think has been the most influential in your work?

I think that overall, printmaking has left the biggest impression on me. Not only is it the medium that I work in most frequently, but it has also greatly influenced the way that I approach image making in general. I especially appreciate that, although most printmaking processes have been around for 500 years or more, there is still an endless amount of experimentation that can happen within these traditional processes which, to me, makes the medium simultaneously contemporary and traditional.

Q: Can you elaborate on how you came to use traditional Japanese scroll mounting techniques and the ways that it has impacted your practice?

I started using Japanese scroll mounting techniques about a year after college when I started making my first large-scale mokuhanga prints. For practical and economic reasons I was printing on relatively thin sekishu paper. The sekishu came on a 39 inch roll that was large enough that I wouldn’t have to piece together multiple pieces of paper for a single image, which made registration simpler, but came with the downside of appearing a little flimsy, lacking a certain substance as a finished print. At the time, I was working at a fine art press in Hawaii and we were using traditional Japanese mounting techniques to execute a suite of 15 woodblock prints that were each 8 feet x 4 feet. I realized that the same process that we were using for those prints could just as easily be applied to my own work. Since then, it has been a process that is inseparable from my regular art practice, freeing me from size constraints, enabling me to use a wider range of papers and even fabric, and to create archival collages, as well as preserve, fortify, and repair delicate and damaged works.

Q: How would you describe your relationship to washi (Japanese paper) and its significance in your work?

Being a printmaker, I have a deep love for traditional processes and quality craftsmanship. To me, washi embodies both of these qualities, while also being incredibly beautiful and an excellent matrix for a variety of printmaking techniques. Each paper has a different personality and it’s vital to the success of a print that the paper is chosen intelligently, with content and process in mind. I use washi consistently for ink painting, mokuhanga, collage, and backing and mounting techniques. While also being aesthetically beautiful, the versatility and strength of washi is what makes it a constant in my artistic practice.

Q: Is there a particular paper that you use more than any other and why?

I genuinely love to experiment with all different types of paper; cotton rag, amate, washi, hanji :you name it, I’ll try it, but ultimately, my paper choice comes down to what I’m using it for. For etching I love a nice gampi (paper) chine colle on Somerset satin 350gsm paper. For mokuhanga, I prefer heavyweight kozo papers with a healthy bit of sizing, most recently I have been printing on the Sakamoto heavyweight paper that you carry and I love it. For my collage work and photo transfers I like to use colored hanji (Korean mulberry paper) and various colored rag papers. Sekishu is still my go-to for backing. With all that said, there are few papers more beautiful and finely crafted than natural heavyweight Gampi Kitakata. Honestly, everything looks better on gampi!

Q: As printmaster for Favianna Rodriguez’s West Oakland studio, we were very excited when you shared your innovations to overcome issues with the fugitive pigments of some hanji (Korean mulberry paper).Can you briefly share with our community your suggestions to deal with this?

First, and most obvious, is to always display work on paper in frames that are fitted with museum-grade glass or OP-3 plexi. Anything that provides conservation grade UV protection on a broad spectrum will prevent fading. For us, the fugitive pigments started to be more problematic when Favianna started collaging with the hanji papers on birch panels. Since these are displayed directly on the wall without a glass or plexi barrier, I started to experiment with different finishes for protection from fading and ultimately settled on Golden brand MSA varnish with UVLS. This is an acrylic solution polymer that incorporates a system of ultraviolet filters and light stabilizers that is advertised as removable for conservation and cleaning purposes, although I have not tried removing it myself.

This varnish is a bit thick and takes two separate coats, two weeks apart, on an absorbent surface such as paper and,

I should warn, is highly toxic and only to be used with appropriate respiratory gear and gloves in a well ventilated space. For aesthetic reasons we have been working with the gloss version of this product, but it is also available in matte and satin. I would recommend choosing your brush carefully as overworking the varnish on the paper surface can cause some abrasion if you’re not careful. I personally like to use brushes that have a good amount of flex and a synthetic bristle, nothing too expensive as this varnish will destroy your brush unless you buy the specific Golden brand solvent for this product. I buy the brushes we use from Home Depot, they usually have a decent selection of chisel-tipped finishing brushes that work great.

Q: Can you describe a typical day in the studio?

I always have several projects at different stages going at any one time so I typically rotate between them. If I’m editioning, everything else gets put on hold and I’m very organized and systematic about working my way through all the steps, from start to finish over several days. If I’m not editioning, first thing, when I get into my studio, I like to do quick brainstorming sketches of new ideas, usually with ink and a brush. This part of my practice is an extension of my sketchbook and is a place where I allow myself to experiment and take risks without judgement. After an hour or two of warming up I transition to more complex pieces that are already in progress and will typically spend the rest of the day focused on a single project like carving woodblocks, planning out a new print, or piecing together intricate collages.  Overall, I try to keep a balance between some of the more tedious tasks with the more creative aspects of my practice, moving between the two when I feel tired or hit a creative wall.

Overall, I try to keep a balance between some of the more tedious tasks with the more creative aspects of my practice, moving between the two when I feel tired or hit a creative wall.